Structure of This Article

This article proceeds as follows:

1. Introduction — What Kind of Structure Do Assets Have?

2. Self-Contained Stock Changes — Instantaneous Movements within a Single Entity

2.1 Single-Entity Co-Generation: Self-Contained Generation of Assets

(1) Generation of Pure Stock Assets

(2) Generation of Securitized Claims

(3) Generation of Fictional Claims

2.2 Single-Entity Co-Extinction: Self-Contained Extinguishment of Assets

3. Unilateral Stock Transfers — One-Way Movements between Entities

3.1 Involuntary Transfer: Without the Sender’s Intent

3.2 Voluntary Transfer: With the Sender’s Intent

4. Bilateral Stock Transfers — Exchange between Entities

5. Self-Contained Flow Cycles — Time-Based Transformations within a Single Entity

5.1 Consumption Flow: Input Aimed at Utility Recovery

5.2 Operational Flow: Input Aimed at Creating Value or Outcomes

6.Inter-Entity Flow Cycles — Time-Based Transactions between Entities

6.1 Lending Flow — Asset Deployment with Repayment Obligations

6.2 Investment Flow — Asset Deployment without Repayment Obligations

7. Asset Typologies and Structures

7.1 Typology of the Debit Side — Asset Status

(1) Absolute Assets

(2) Relational Assets (Repayment-Based Claims)

(3) Investment Assets (Return-Based Claims)

7.2 Typology of the Credit Side — Sources of Assets

(1) Relational Liabilities

(2) Relational Capital

(3) Absolute Capital

7.3 Structural Overview of Asset Typologies

8. Conclusion — The Path to Surplus

<Appendix> Visual Summary — Asset Movement & Typology Framework

Asset Movement Typologies (4 Quadrants, 8 Types)

Asset Typologies (6 Types)

1. Introduction — What Kind of Structure Do Assets Have?

In this post, we turn our attention to the forms (structures) that these generated assets take on within the BS, and how they can be systematically classified into types—specifically, into eight distinct movement types organized across four structural quadrants.

Assets are not merely “things” or “money.” Rather, they are entities that hold value either through self-contained mechanisms or through relationships with others, and that exhibit particular structural patterns of change over time.

To explore these patterns, this post classifies asset movements along two key axes:

• Single-Entity / Inter-Entity — Whether or not the change involves another party

• Stock / Flow — Whether the change is instantaneous or involves a time-based process

These two axes define four structural quadrants, within which we identify eight movement types—each representing a specific pattern of asset behavior.

These axes correspond to the “Relation” and “Structure” layers of the Three-Layer BS Framework (Domain × Structure × Relation) introduced in the previous post. Through these lenses, we aim to clarify the full picture of assets and present a comprehensive framework for understanding them.

Ultimately, this structural understanding leads us to a deeper question: Can assets truly increase? In other words, where does surplus come from—and what kind of structure makes it possible?

The classification presented here lays the groundwork for addressing that question in the next post.

2. Self-Contained Stock Changes — Instantaneous Movements within a Single Entity

In Structural Analysis ①: The Genesis of Assets, we examined how assets emerge on the balance sheet (BS), using the concepts of Single-Entity Co-Generation and Inter-Entity Co-Generation. As described there, BS assets originate with the generation of stock assets (both pure stock assets and stock-like flow assets) through Single-Entity Co-Generation.

These stock assets then lead to the creation of flow assets: either through the Inter-Entity Co-Generation that arises when pure stock assets are externally deployed, or through the internal activation of flow functions when stock-like flow assets are mobilized toward others.

See: Structural Analysis (1) — Where Stock and Flow Begin for details.

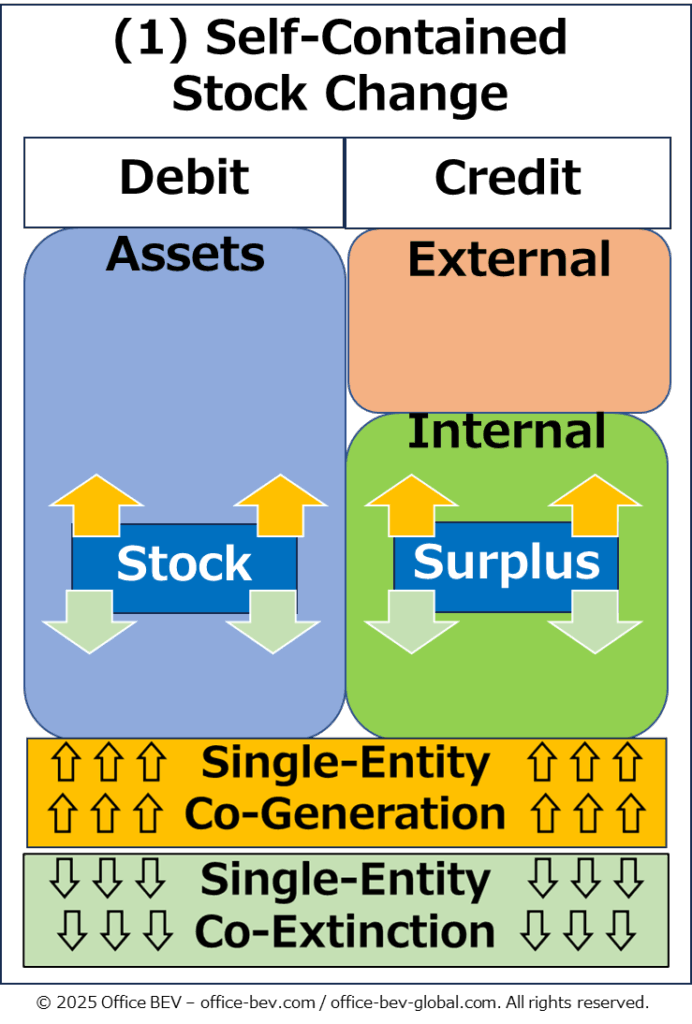

At the foundation of asset dynamics lies a basic pattern: stock-based assets can both emerge and disappear within a single-entity BS.

We refer to these instantaneous structural events as Self-Contained Stock Changes—a category of stock-type transformations that occur without external involvement.

2.1 Single-Entity Co-Generation: Self-Contained Generation of Assets

Asset generation begins within a single-entity BS through a process known as Single-Entity Co-Generation.

As outlined in the previous analysis, there are three primary forms of this asset generation, categorized by the nature of the asset produced:

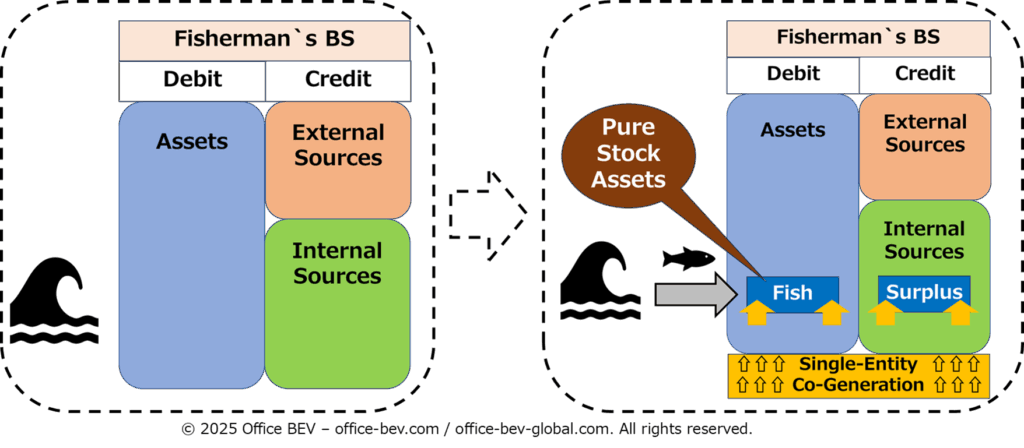

(1) Generation of Pure Stock Assets

These assets carry physical and determinable value and are acquired through direct interaction with the natural environment or personal labor—such as gathering, mining, harvesting, fishing, or hunting.

Example: A fisherman catches fish in the sea.

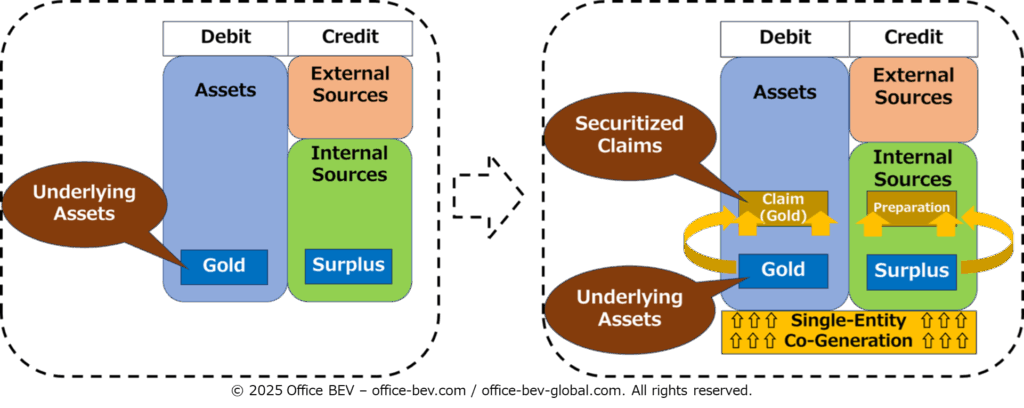

(2) Generation of Securitized Claims

Here, a claim to future delivery is created using a pure stock asset as the underlying asset, meaning the original resource (such as gold) that supports the value of the securitized claim. This process essentially turns the asset into a transferable right.

Example: A claim on a gold bar in storage.

(Image)

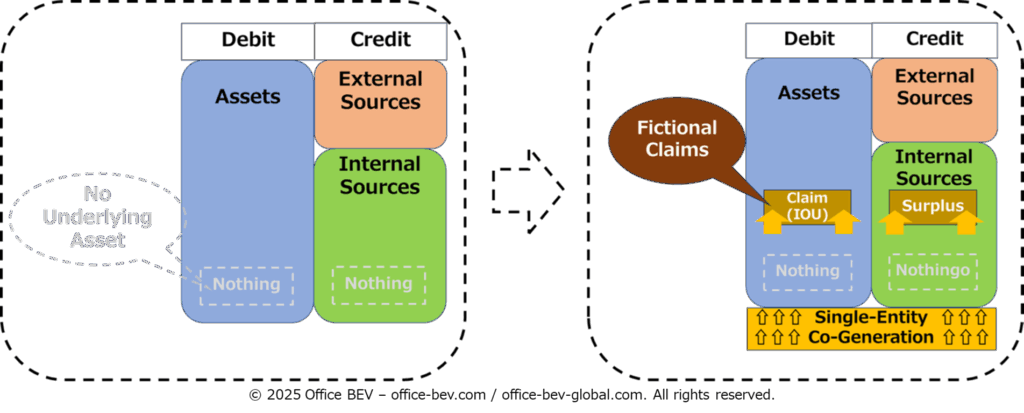

(3) Generation of Fictional Claims

Here, a claim is created without any underlying asset at the time of issuance. Instead, it relies entirely on trust, expectation, or projected future value. This process essentially brings a right into existence through belief alone, turning anticipated future value into a recognizable asset.

Example: An IOU (“I owe you”) issued without collateral.

(Image)

Keywords: No Underlying Assets, Fictional Claims, Claim (IOU) — a right based on anticipated labor or value creation, issued with nothing but mutual belief.

Single-Entity Co-Generation is a self-contained and instantaneous stock-based transformation that takes place entirely within a single-entity BS, without involving other parties (Single-Entity × Stock).

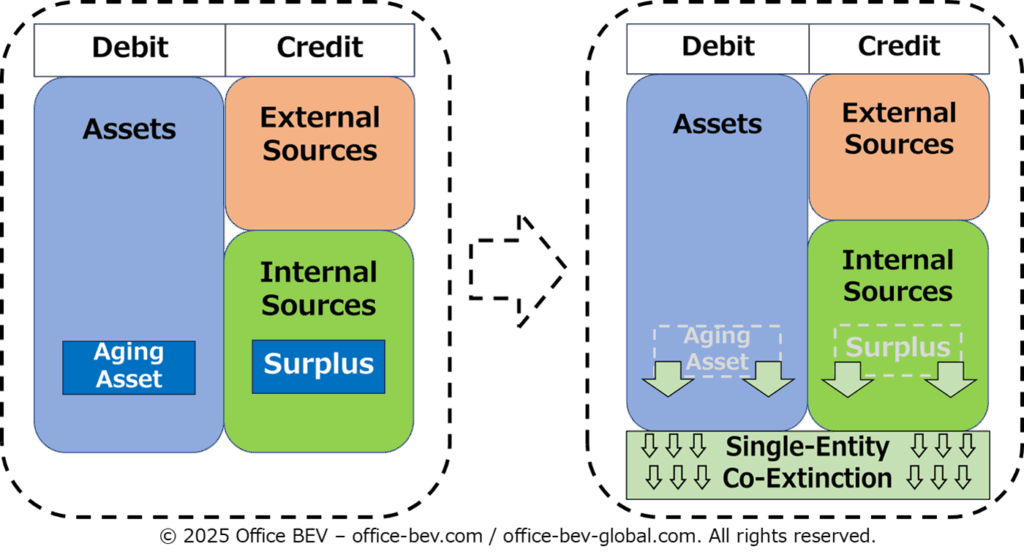

2.2 Single-Entity Co-Extinction: Self-Contained Extinguishment of Assets

Single-Entity Co-Extinction is the inverse of generation: assets are extinguished entirely within the entity’s BS, without involving any external party.

Typical examples include asset destruction caused by natural disasters or the disposal of obsolete equipment.

Single-Entity Co-Extinction is a self-contained and instantaneous stock-based transformation that takes place entirely within a single-entity BS, without involving other parties (Single-Entity × Stock).

Example: Disposing of an aging asset such as an outdated machine (with some remaining surplus value).

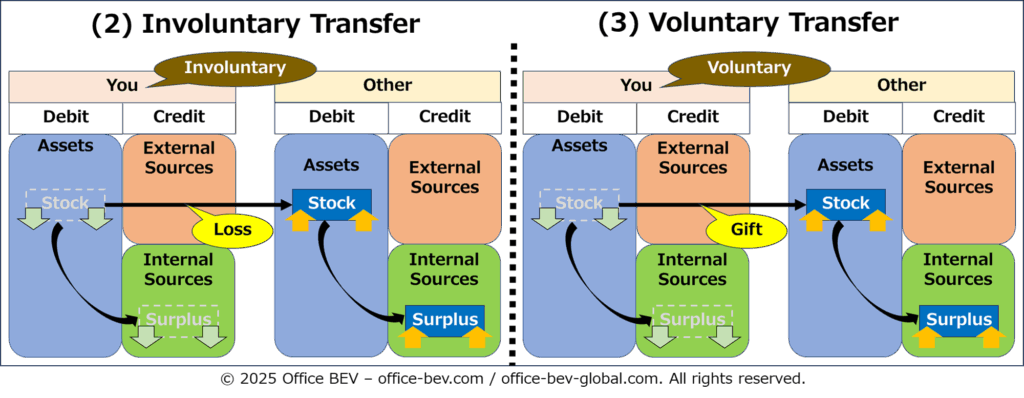

3. Unilateral Stock Transfers — One-Way Movements between Entities

Assets that originate through Single-Entity Co-Generation do not always remain within the originating entity. In many cases, they are transferred outward—sometimes by force, sometimes by will—into the hands of others.

This section examines one-way inter-entity asset transfers, where an asset moves from one balance sheet to another without any reciprocal exchange or flow-based relationship. These movements are structurally different from generation or extinction and are best understood as immediate, stock-based transfers between entities.

There are two distinct types:

- Involuntary Transfer: The asset leaves the original entity without the sender’s intent.

- Voluntary Transfer: The asset is given intentionally by the sender, without expecting anything in return.

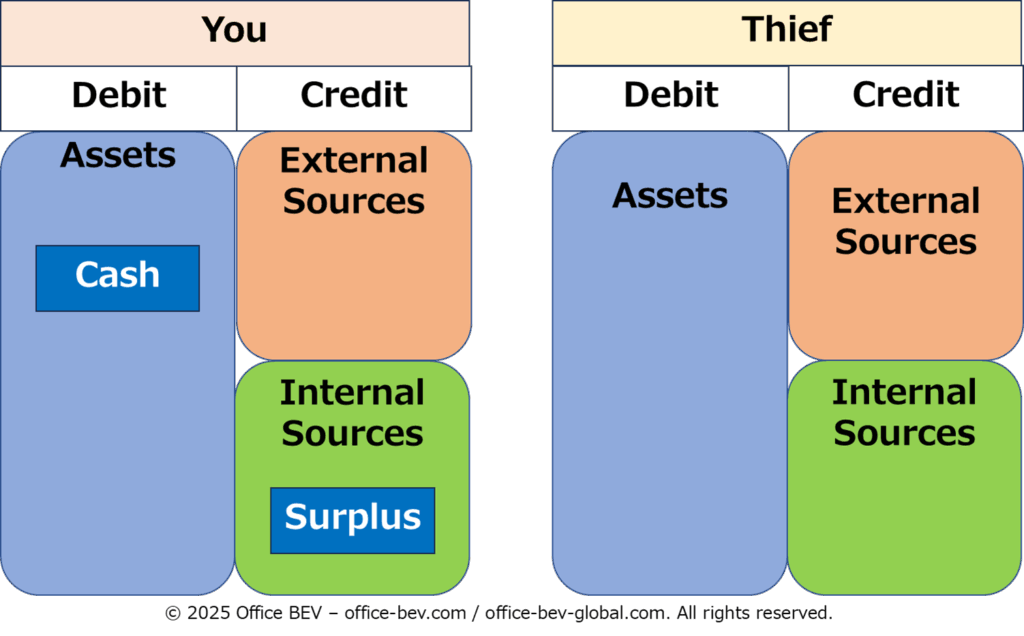

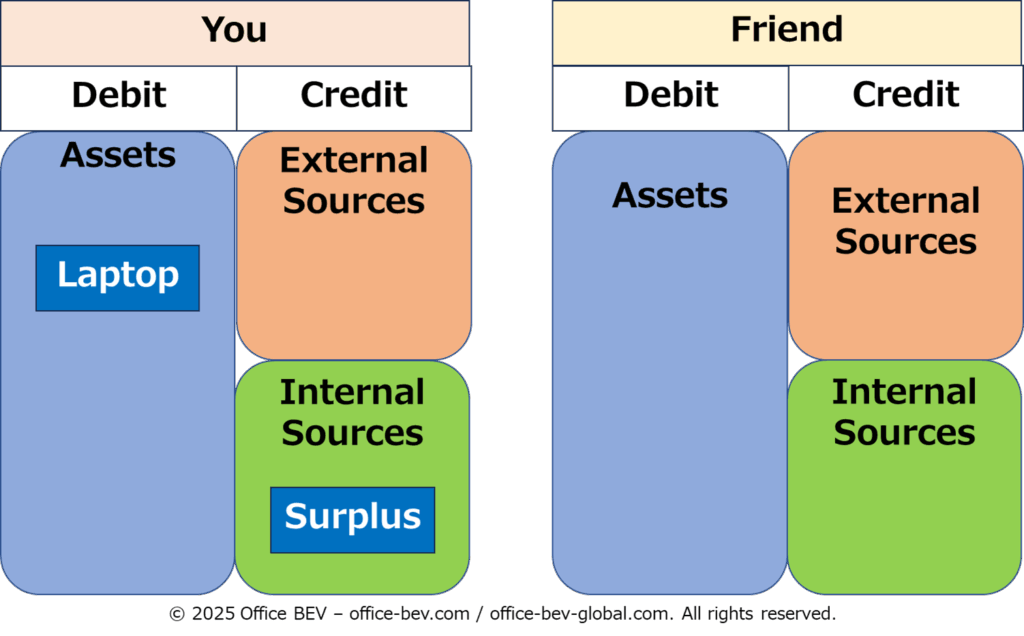

3.1 Involuntary Transfer: Without the Sender’s Intent

In an involuntary transfer, an asset is taken from one entity and ends up on another’s balance sheet without the consent or intention of the original holder.

Example: A thief steals cash from someone.

<Before>

<After>

Here, the asset is transferred from one BS to another without mutual agreement. There is no flow-based structure (such as claims or obligations), and the transfer is completed immediately. It remains a stock-based inter-entity movement.

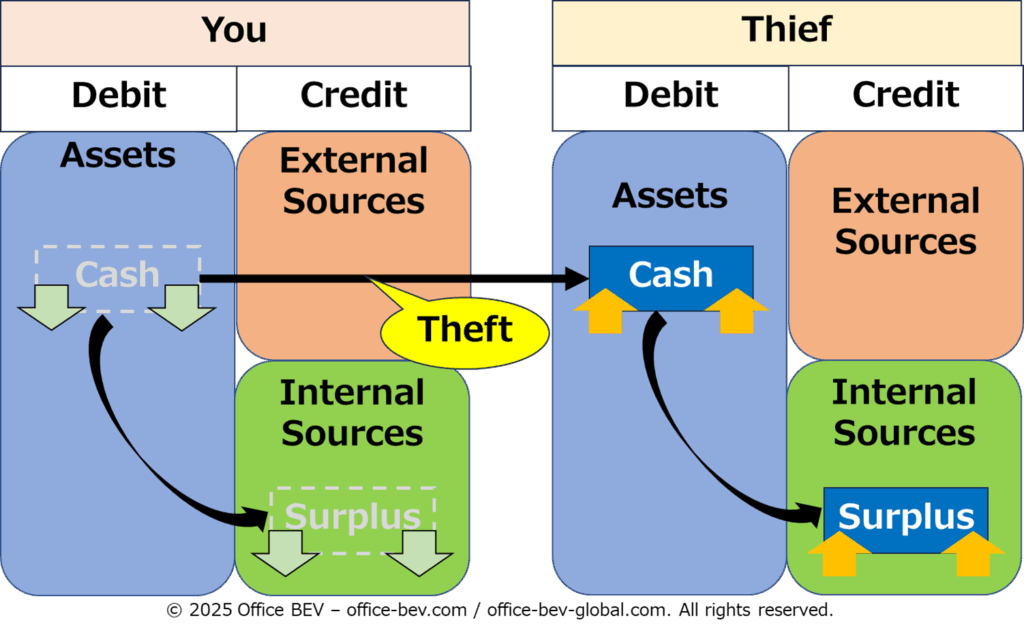

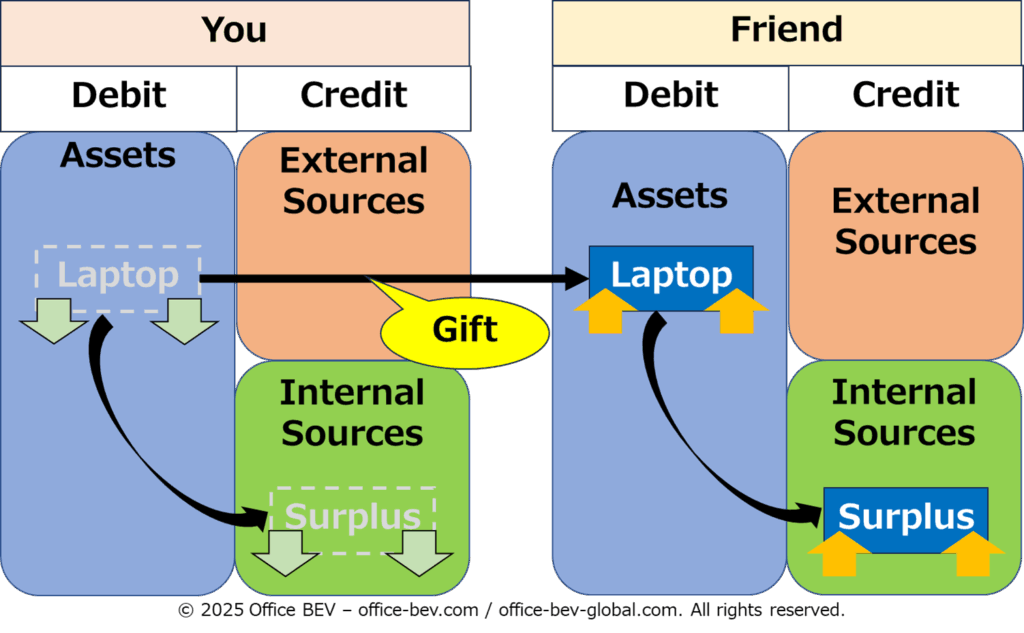

3.2 Voluntary Transfer: With the Sender’s Intent

In contrast, a voluntary transfer occurs when the asset holder intentionally gives the asset to another party. While the movement remains unilateral, the key distinction lies in the sender’s deliberate will.

Common examples include gifts, donations, and subsidies.

Example: You give your friend a laptop.

<Before>

<After>

Despite the intention being present in this case, structurally it is still an inter-entity, stock-based, one-way movement with no reciprocal flow structure.

In both types of transfers, the asset moves from one balance sheet to another without creating any flow-based relationship—such as claims or obligations.

As such, these cases are best understood as Inter-Entity Stock Transfers, distinct from any form of asset generation or extinction. (Inter-Entity × Stock)

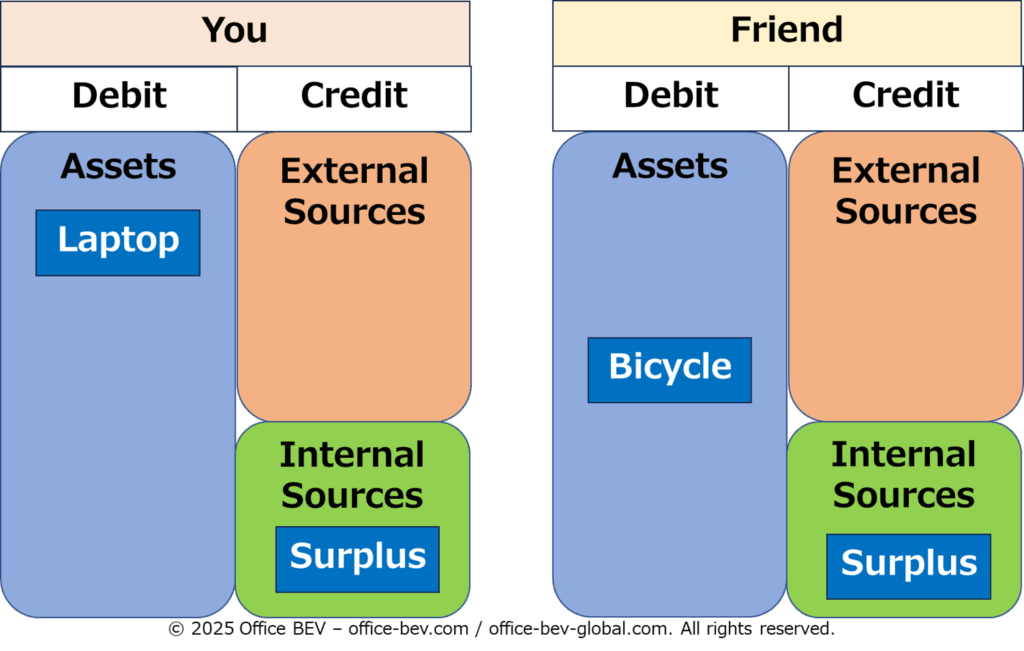

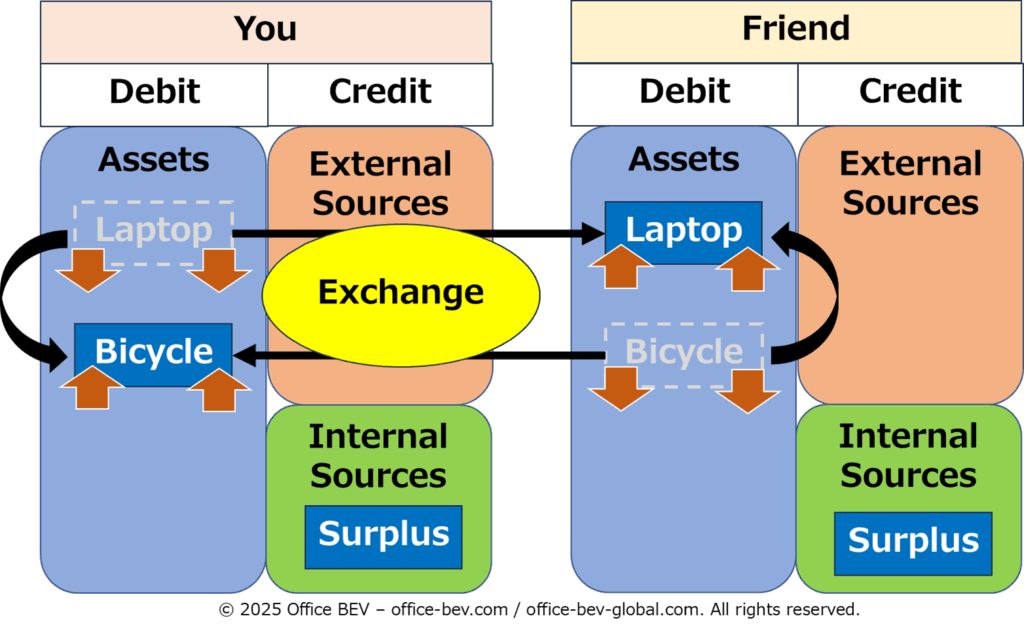

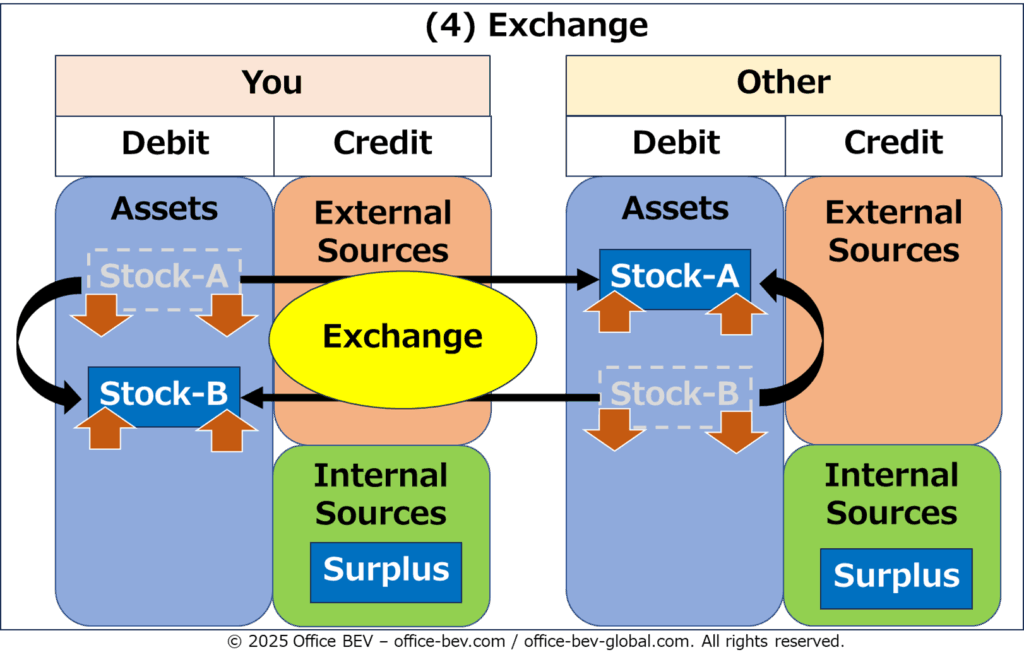

4. Bilateral Stock Transfers — Exchange between Entities

Following the examination of one-way asset transfers, we now turn to bilateral transfers, where both parties exchange assets in a mutually agreed transaction. In this post, we refer to this structure simply as an exchange.

This type of transfer is characterized by a reciprocal movement of stock assets between two entities.

Example: You exchange your laptop for your friend’s bicycle.

<Before>

<After>

An exchange is essentially the bilateral counterpart to the one-way transfers discussed previously—transforming a one-sided movement into a mutual exchange of value. Structurally, it falls under the same category: Inter-Entity × Stock.

Notably, this movement does not involve any generation or extinction of assets. Each party’s asset is simply replaced by the other’s, and the total asset value on each balance sheet remains unchanged.

So far, we’ve examined stock-based asset movements that are completed instantly, without any time-based flow structure:

- Self-Contained Stock Changes within a single entity (Single-Entity × Stock)

- One-Way Transfers between entities (Inter-Entity × Stock)

- Exchanges between entities (Inter-Entity × Stock)

Next, we will shift our focus to a different kind of movement—those that unfold over time.

These are flow-based asset transformations, which involve not just the movement of assets, but also the passage of time and the emergence of relational structures such as claims and obligations.

5. Self-Contained Flow Cycles — Time-Based Transformations within a Single Entity

We now turn to flow-based asset transformations. The first structure to examine is when a single entity deploys its own assets internally for future recovery. This is what we call a Self-Contained Flow Cycle.

In this configuration, assets held within the single-entity BS are deployed into a flow process initiated by the entity itself. Over time, the input undergoes transformation—whether through internal use or productive activity—and is ultimately recovered as value.

While the process remains internally initiated and managed, it may incorporate external interactions as part of its transformation path. This constitutes a self-directed, time-based cycle grounded in the entity’s own asset operations.

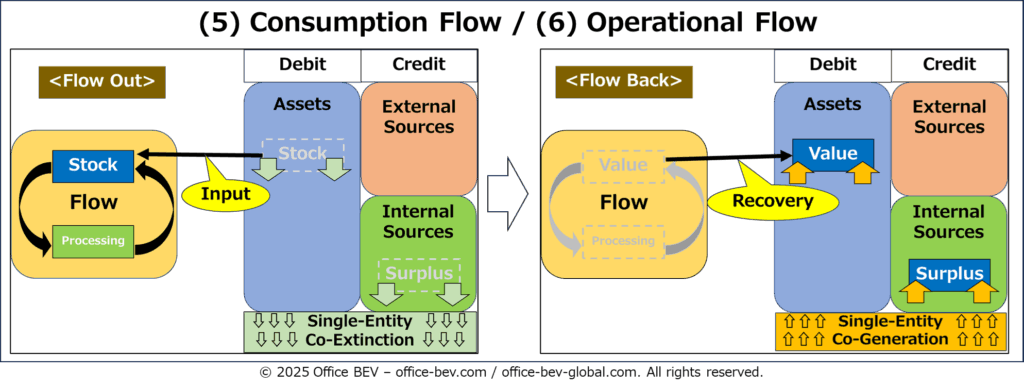

There are two main types of Self-Contained Flow Cycles:

- Consumption Flow, typically found in individuals, aimed at obtaining physiological or psychological utility.

- Operational Flow, aimed at creating future outcomes such as economic value, knowledge, or personal development.

Let’s examine each in turn.

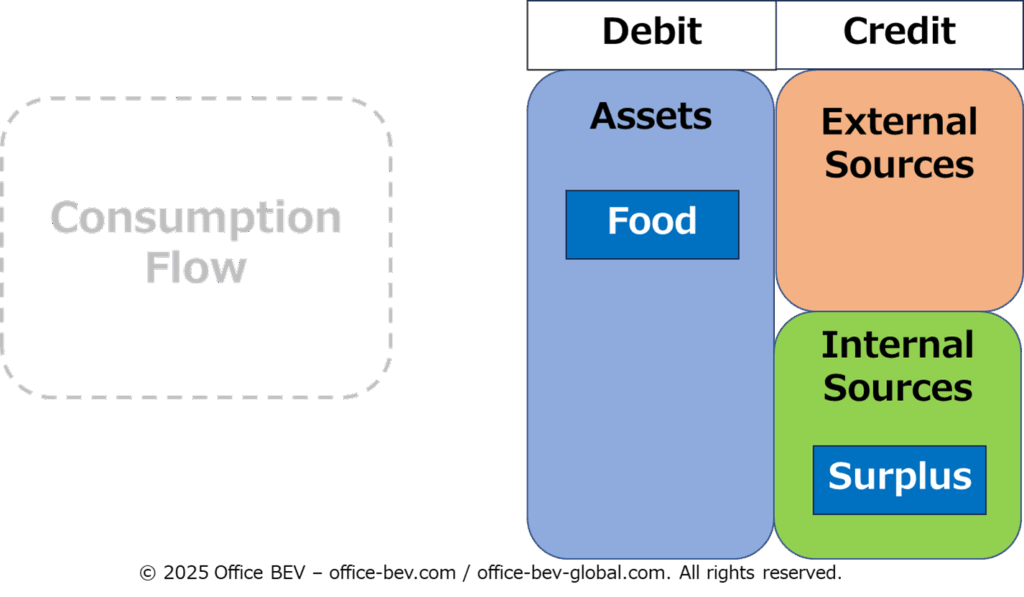

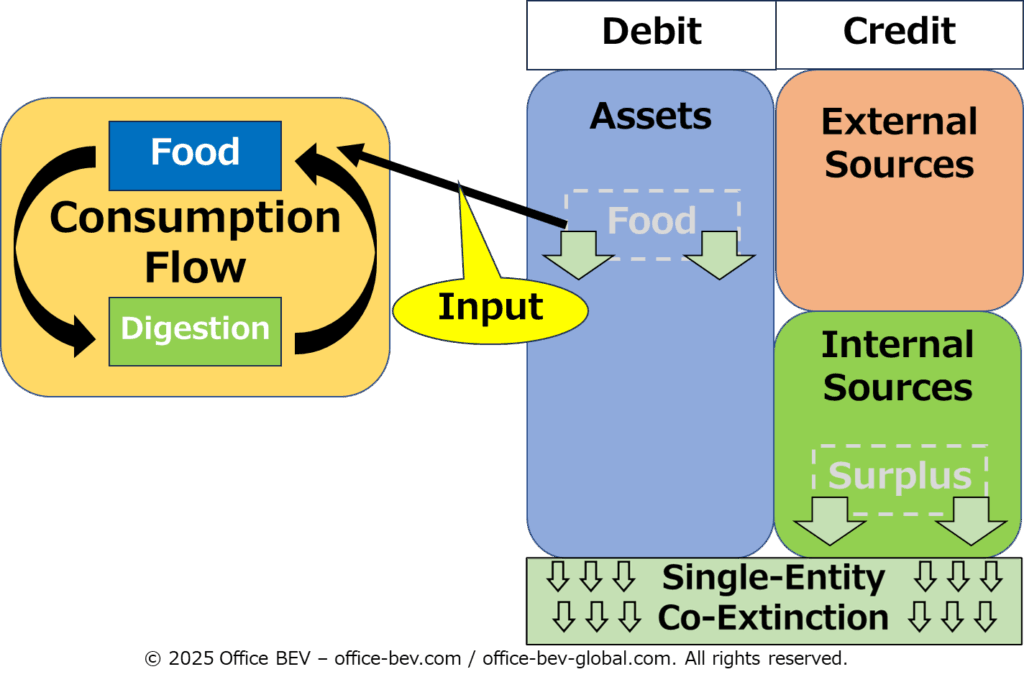

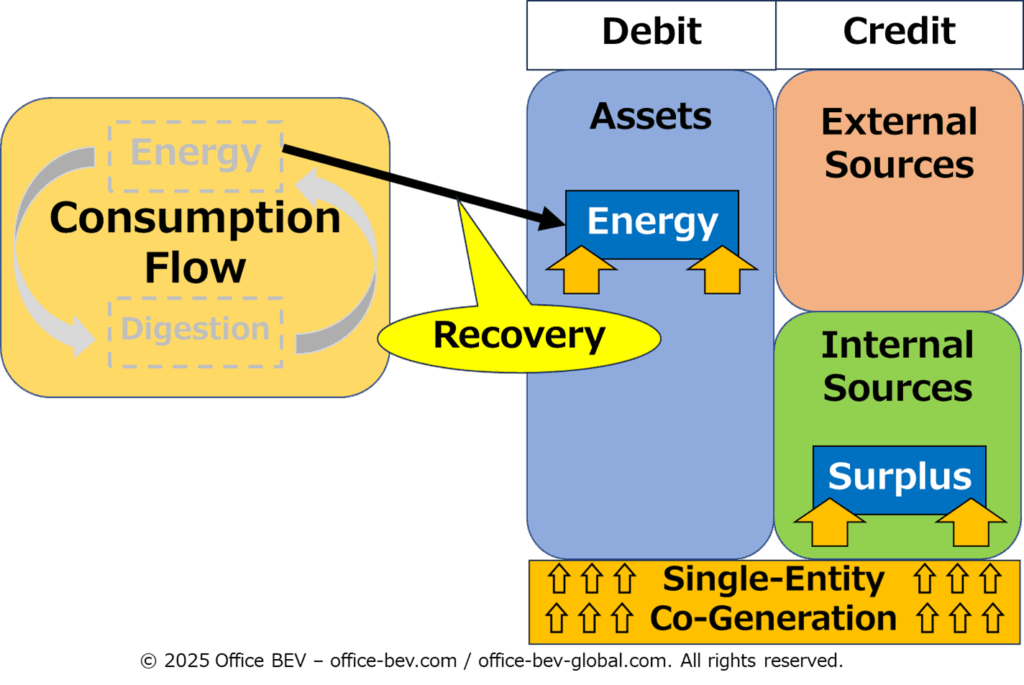

5.1 Consumption Flow: Input Aimed at Utility Recovery

A Consumption Flow typically occurs when a natural person invests assets in themselves with the goal of recovering utility.

The recovered value takes the form of:

- Physiological utility (e.g., nourishment, rest)

- Psychological utility (e.g., enjoyment from music or entertainment)

In both cases, the asset undergoes a time-bound transformation, and the value is recovered internally within the same BS.

Example: You consume food.

<Before>

<Flow Out>

<Flow Back>

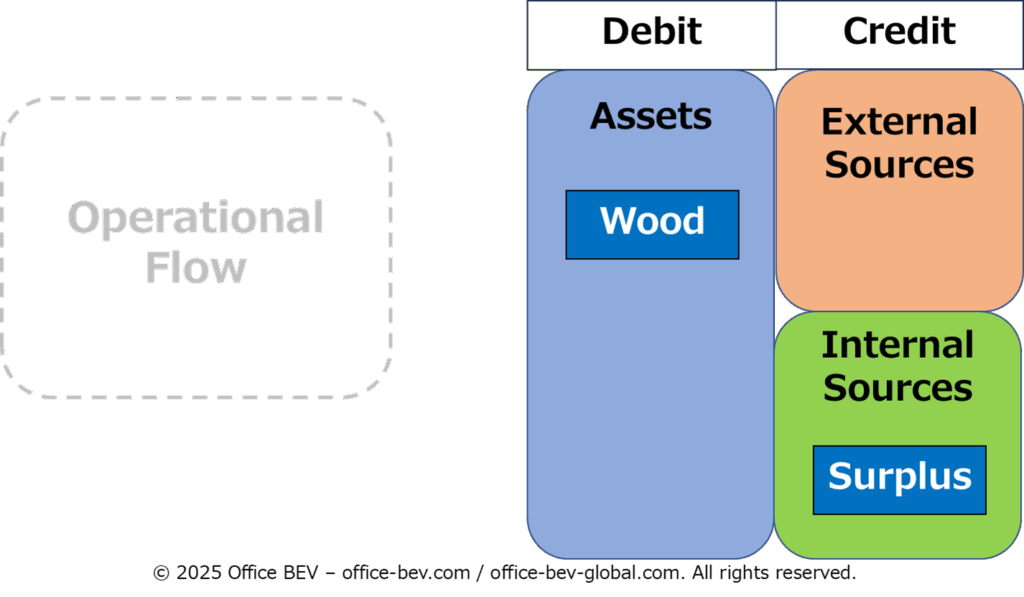

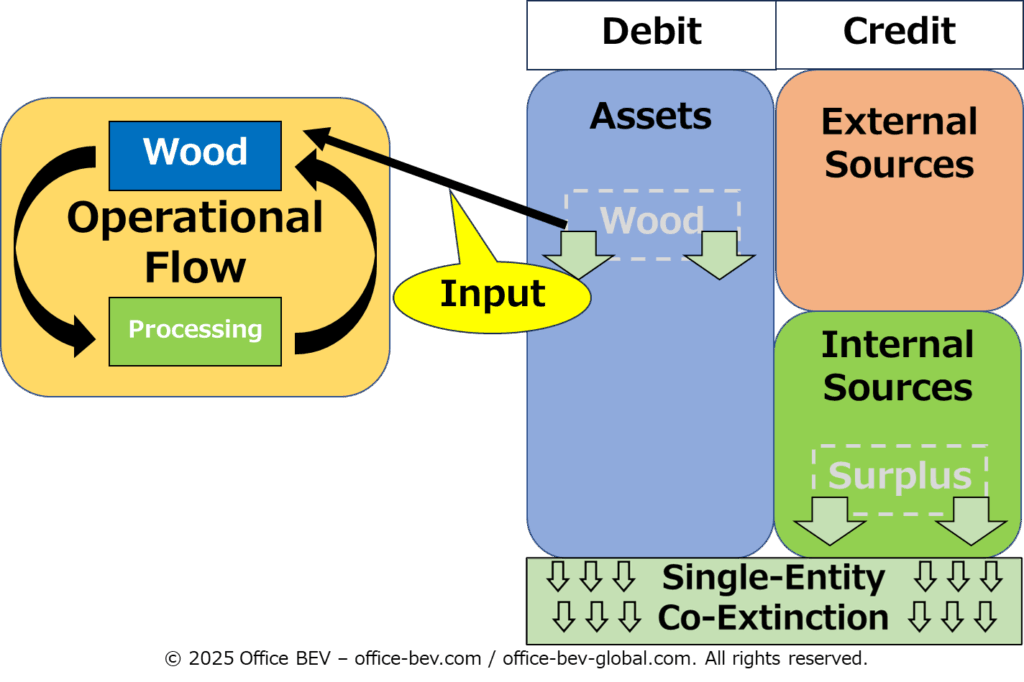

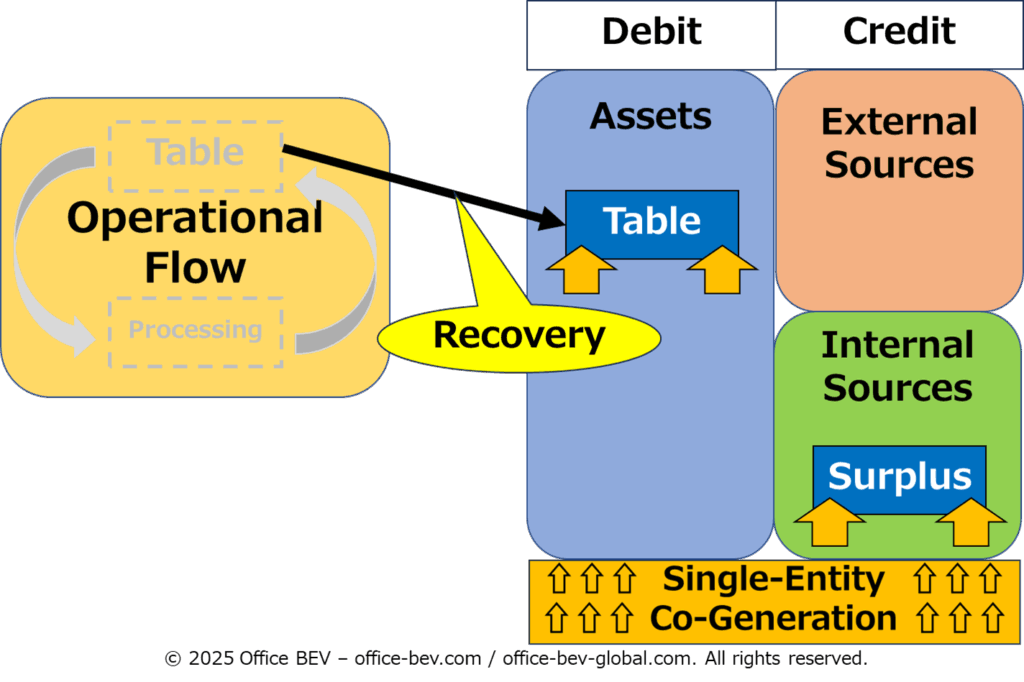

5.2 Operational Flow: Input Aimed at Creating Value or Outcomes

An Operational Flow occurs when an entity invests resources into developing internal capabilities—such as business activities, knowledge, skills, or social infrastructure—with the intention of realizing future gains.

The recovered value can include economic returns, but also non-monetary outcomes like intellectual or social capital.

The key structural feature here is a time-based cycle: investment is followed by a process of transformation, which culminates in recovery.

Example: You build a table from raw wood.

<Before>

<Flow Out>

<Flow Back>

In both Consumption and Operational flows, the transformation is initiated and managed by the entity itself, occurring over time within the scope of its own balance sheet.

These are classified as Single-Entity × Flow structures—time-based transformations distinct from the instantaneous nature of stock-type movements.

6.Inter-Entity Flow Cycles — Time-Based Transactions between Entities

In contrast to the Self-Contained Flow Cycle, where assets are deployed and recovered within a single entity, this section explores a relational structure: a flow-based process in which assets are deployed to an external party, generating a relational claim, and later recovered.

We refer to this structure as an Inter-Entity Flow Cycle.

When an asset is deployed to another entity, the act initiates a relational structure known as Inter-Entity Co-Generation.

This refers to a process in which a stock asset is deployed to an external party, and—through that act—a pair of flow-based assets is simultaneously generated in the relational space between the sender and the recipient:

a Claim, recorded on the sender’s balance sheet as a right to receive something back, and

an Obligation, recorded on the recipient’s balance sheet as a duty to return value in the future.

This Claim/Obligation structure is the defining feature of flow-based asset relationships, and serves as a foundational concept throughout the remainder of this analysis.

For a detailed discussion of how such claims and obligations emerge, see:

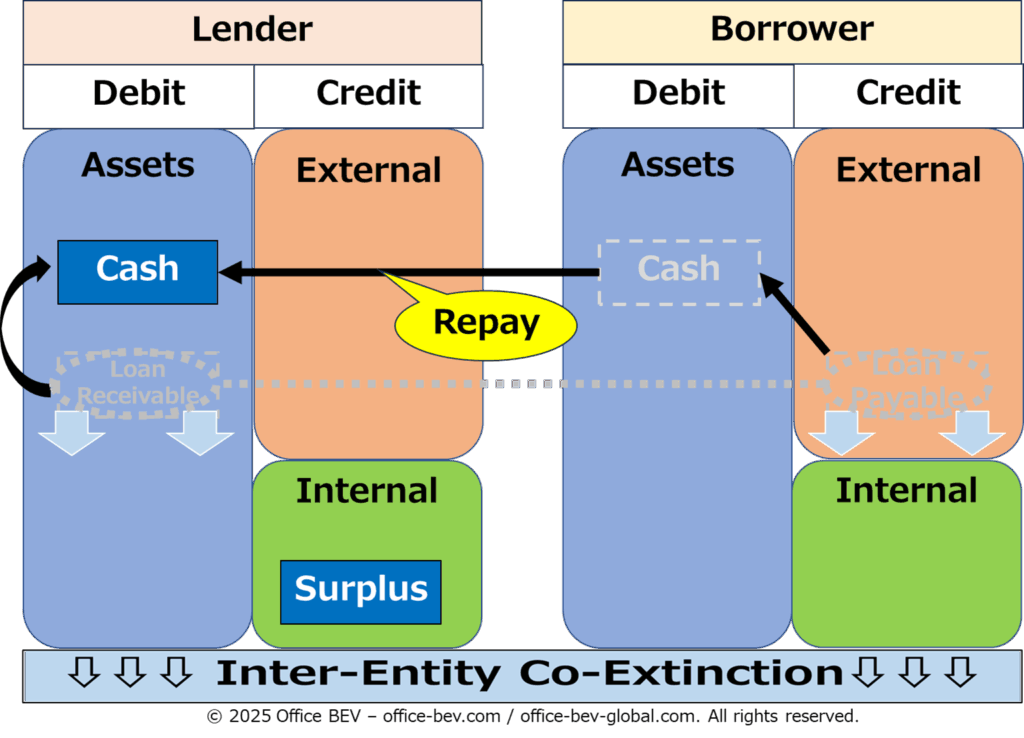

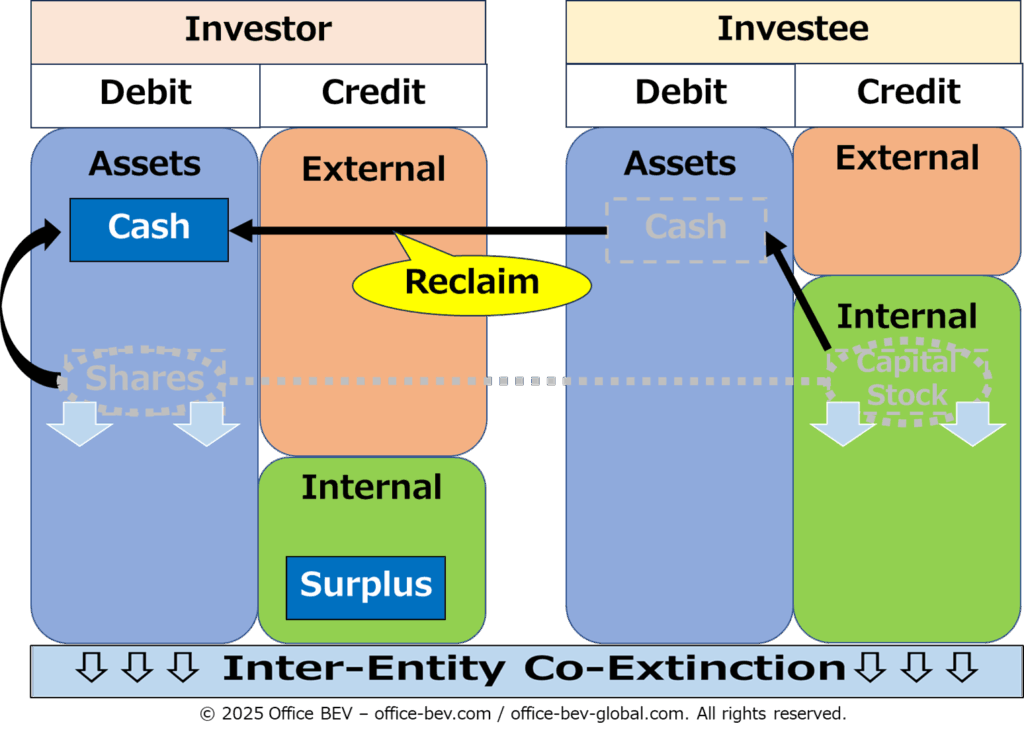

In an Inter-Entity Flow Cycle, the generated claim and obligation persist for a certain duration, and are eventually extinguished through the return or settlement of the originally deployed asset—completing the relational cycle through what we call Inter-Entity Co-Extinction.

This structure comes in two primary forms:

- Lending Flow — where the recipient incurs a formal obligation to return the asset.

- Investment Flow — where the recipient assumes no such obligation, but a return is expected based on future performance.

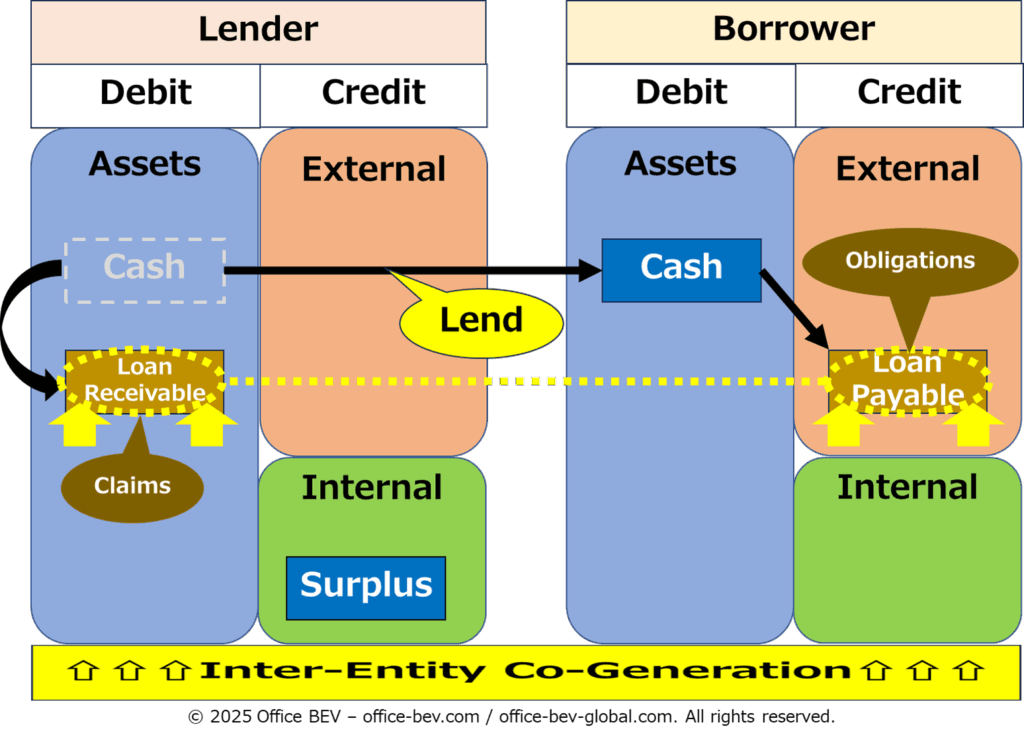

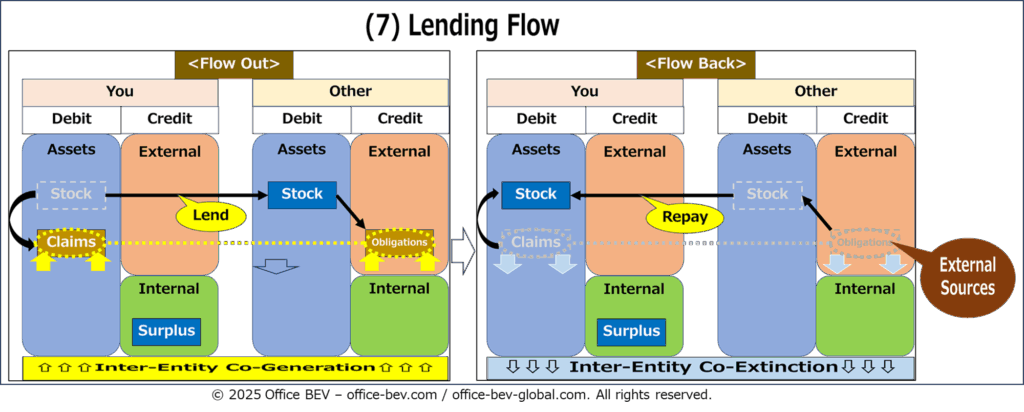

6.1 Lending Flow — Asset Deployment with Repayment Obligations

A Lending Flow occurs when an asset is transferred to another party with a formal repayment structure in place.

At the moment of lending, Inter-Entity Co-Generation is activated:

- The borrower incurs a legal obligation to repay (a liability).

- The lender acquires a claim to receive repayment (an asset).

After a set period, Inter-Entity Co-Extinction occurs through repayment, concluding the relational structure.

The defining feature of this flow is that repayment is institutionally guaranteed.

On the borrower’s balance sheet, the obligation is categorized as “External Sources” — indicating externally sourced liabilities.

Example: Lending cash to another party

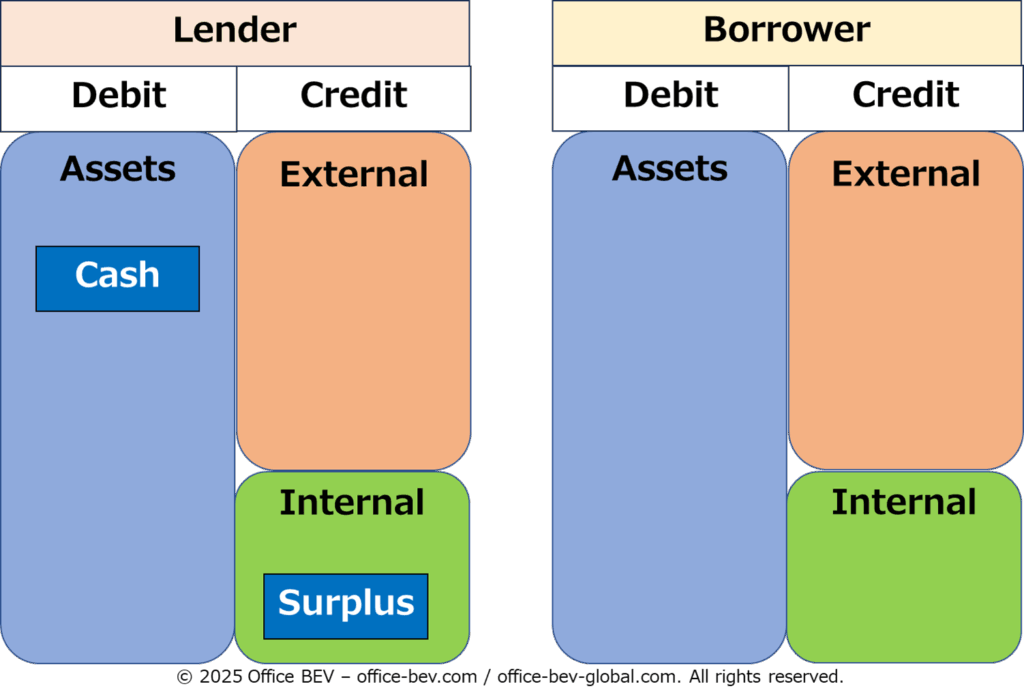

<Before> — Prior to lending

<Flow Out> — Lending initiated

<Flow Back> — Repayment received

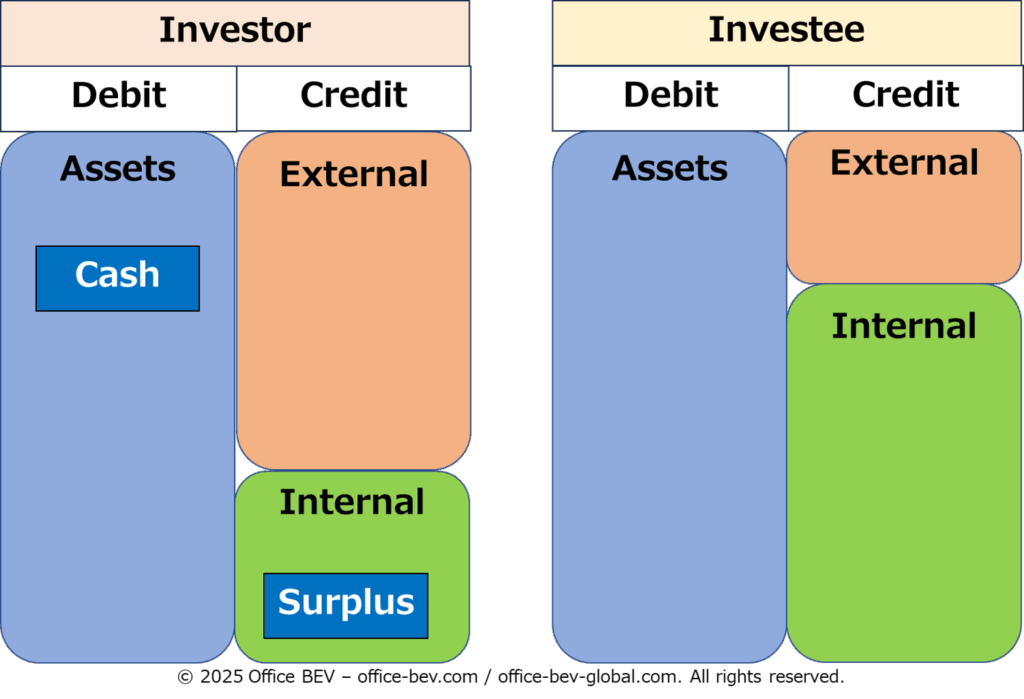

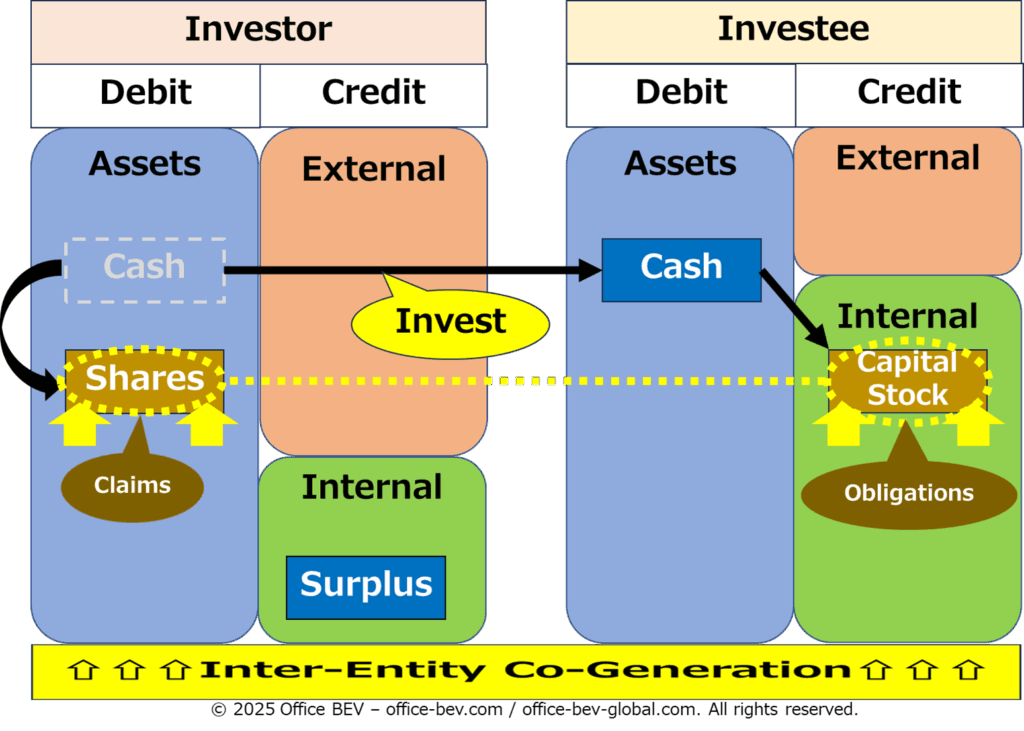

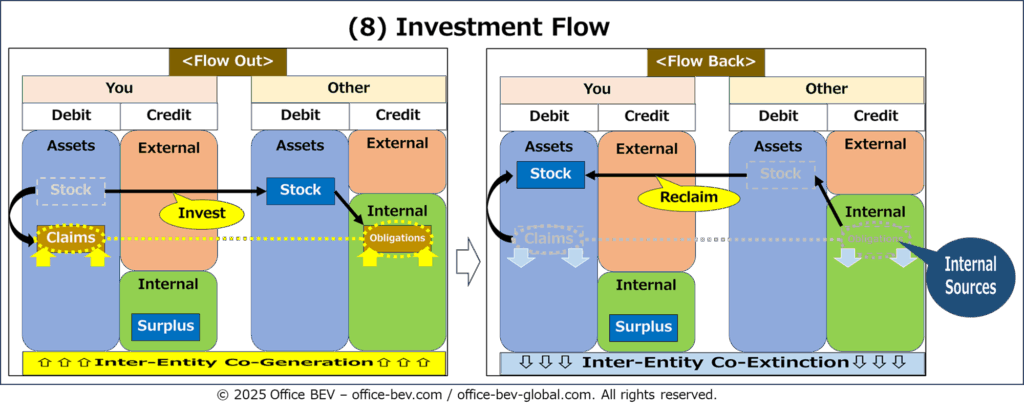

6.2 Investment Flow — Asset Deployment without Repayment Obligations

An Investment Flow involves deploying assets to another entity without any contractual obligation of repayment, but with the expectation of future returns.

This also initiates Inter-Entity Co-Generation: a claim-obligation pair is formed, but the outcome is inherently uncertain.

- The value recovered may be greater than, less than, or equal to the initial investment.

- In some cases, no return is realized at all.

Here, the structural emphasis is on non-obligatory, performance-based recovery rather than debt repayment.

On the recipient’s balance sheet, the incoming asset is categorized as “Internal Sources” — recorded under capital accounts such as Surplus or Preparation.

Example: Investing in another party’s venture

<Before> — Prior to investment

<Flow Out> — Investment initiated

<Flow Back> — Return received

Both Lending and Investment flows are relational cycles based on Inter-Entity Co-Generation and Co-Extinction, driven by time-based transformation and recovery.

Together, they represent Inter-Entity × Flow structures—relational processes that differ from immediate transfers or self-contained internal flows.

Having explored the various patterns of how assets change form and move across balance sheets, we now turn to the next step: how these assets are categorized on the balance sheet itself. What distinguishes one asset type from another—and how does this reflect their origins and relationships?

7. Asset Typologies and Structures

Having examined the various ways assets move and transform, we now turn to the structural classification of assets on the balance sheet—both on the debit side (asset status) and the credit side (asset sources).

This classification draws from two key layers of the Three-Layer BS Framework:

- Structure (Stock / Flow) — whether the asset exists independently or arises over time through interaction

- Relation (Single-Entity / Inter-Entity) — whether the asset depends on external relationships

Using these axes, we present a logical framework that classifies each asset according to its structural form—either stock-based or flow-based—and the relational context in which it arises.

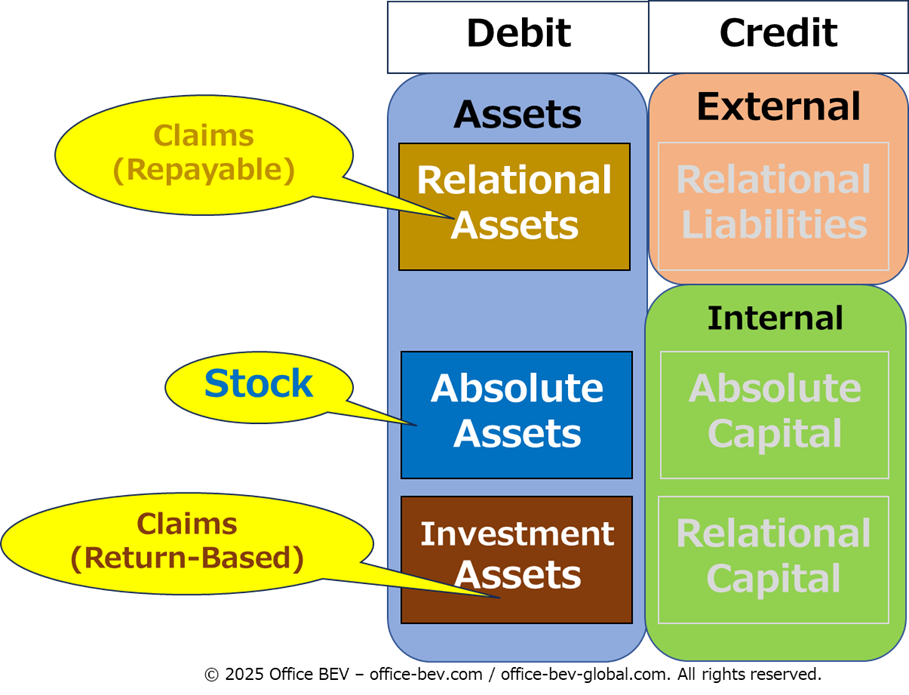

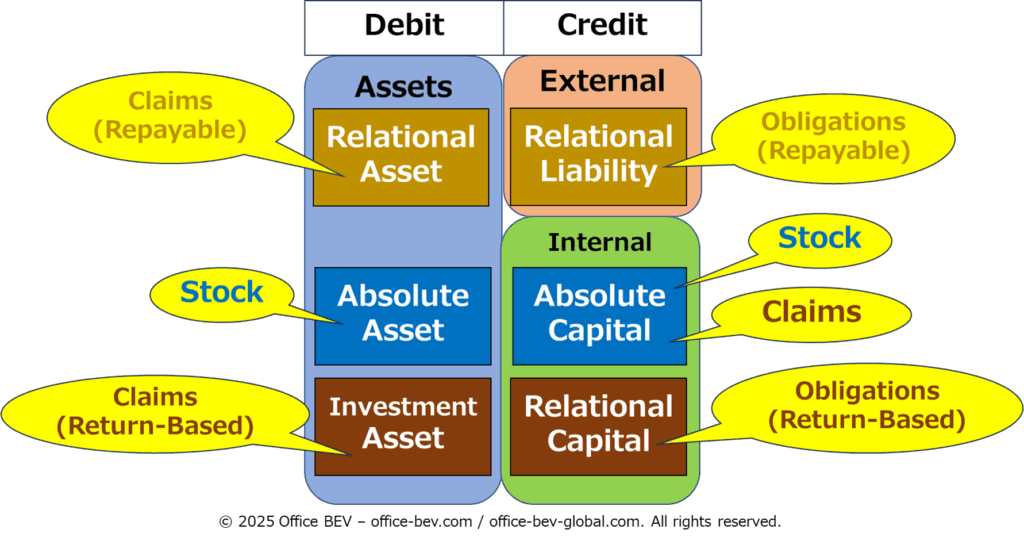

7.1 Typology of the Debit Side — Asset Status

The debit side of the balance sheet represents the asset status of the entity—that is, the current structural state of what the entity holds or controls. These can first be divided into:

- Stock assets, which exist independently and require no ongoing relationship, and

- Flow assets, which arise from inter-entity flows and take the form of claims in a relational structure.

Flow-based claims themselves are further divided according to their origin:

- If they arise from Lending Flows, they represent enforceable repayment rights.

- If they stem from Investment Flows, they reflect non-obligatory expectations of future value.

This yields the following three categories of debit-side assets:

(1) Absolute Assets

Assets that exist independently and can realize value without any external party. These are stock-based and do not involve any flow structure.

Examples: Cash on hand, equipment, inventory, owned land.

(2) Relational Assets (Repayment-Based Claims)

Assets that arise through Lending Flows, where the counterparty bears a formal repayment obligation.

Examples: Loans receivable, accounts receivable.

(3) Investment Assets (Return-Based Claims)

Assets that arise through Investment Flows, where the counterparty has no legal repayment obligation but is expected to deliver returns or outcomes in the future.

Examples: Equity investments, contributed capital.

<Debit-side asset typology>

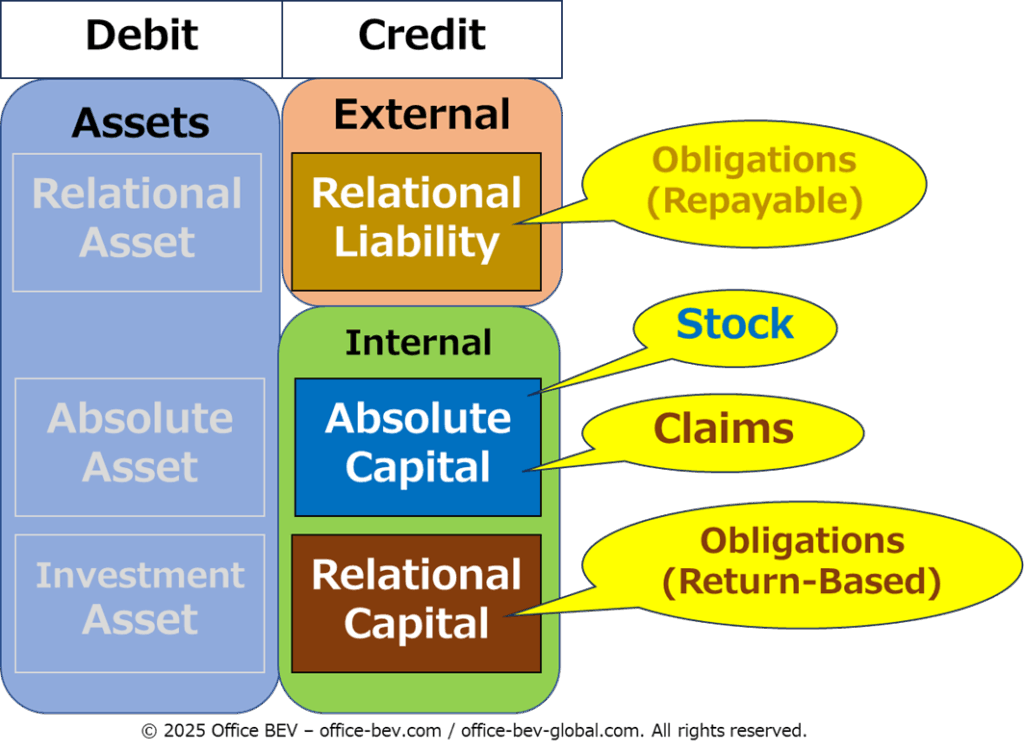

7.2 Typology of the Credit Side — Sources of Assets

The credit side of the balance sheet reflects the sources of the assets. These sources correspond to the asset types on the debit side, especially for flow assets—since every claim on one balance sheet must be mirrored by a corresponding obligation on another.

Accordingly, we classify credit-side sources into three types:

(1) Relational Liabilities

Obligations arising from Lending Flows—where the entity owes repayment to another party. These are always externally sourced and represent inter-entity liabilities.

Examples: Borrowings, accounts payable, deposits held for others.

(2) Relational Capital

Obligations arising from Investment Flows, where there is no repayment obligation, but the entity is entrusted with capital and held accountable for future performance (e.g., dividends or governance rights).

Examples: Contributed capital, equity shares.

(3) Absolute Capital

Internally sourced capital that involves no obligations to external parties. This typically takes the form of stock-based capital—resources either generated independently or converted from existing rights.

This may include:

- Stock-based surpluses generated independently (e.g., retained earnings), or

- Claims converted into stock capital (e.g., receiving shares as capital contribution).

Examples: Retained earnings, capital created from the transfer of investment claims.

<Credit-side source typology>

The credit side of the BS is often seen through the lens of “external vs. internal” sourcing—External Sources (liabilities to others) vs. Internal Sources (self-held capital or entrusted funds without repayment obligation). Within this framework:

• Relational Liabilities are External Sources (obligations to others)

• Relational Capital and Absolute Capital are Internal Sources (self-held or entrusted with no return obligation).

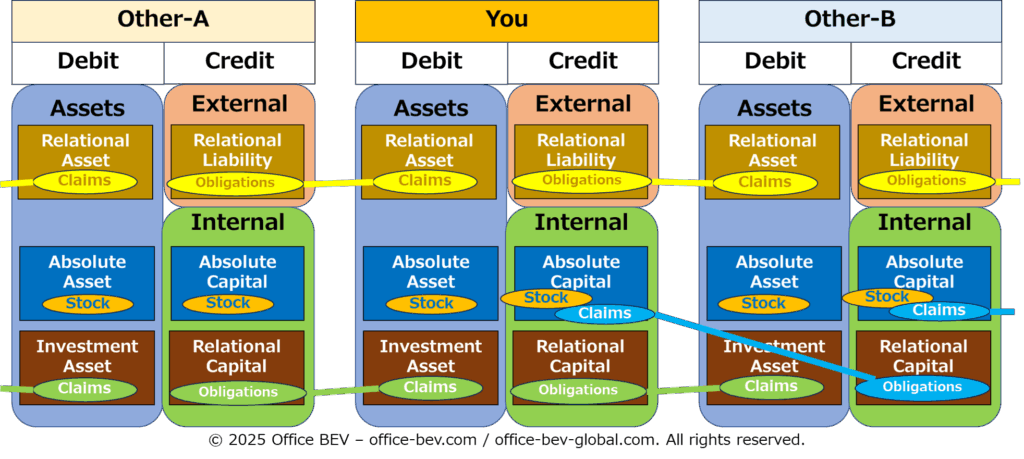

7.3 Structural Overview of Asset Typologies

To conclude this section, by combining the three debit-side types (Asset Status) and the three credit-side types (Asset Sources), and mapping them to the flow-based relationships in which they arise, we obtain a complete structural overview of asset typologies on the BS.

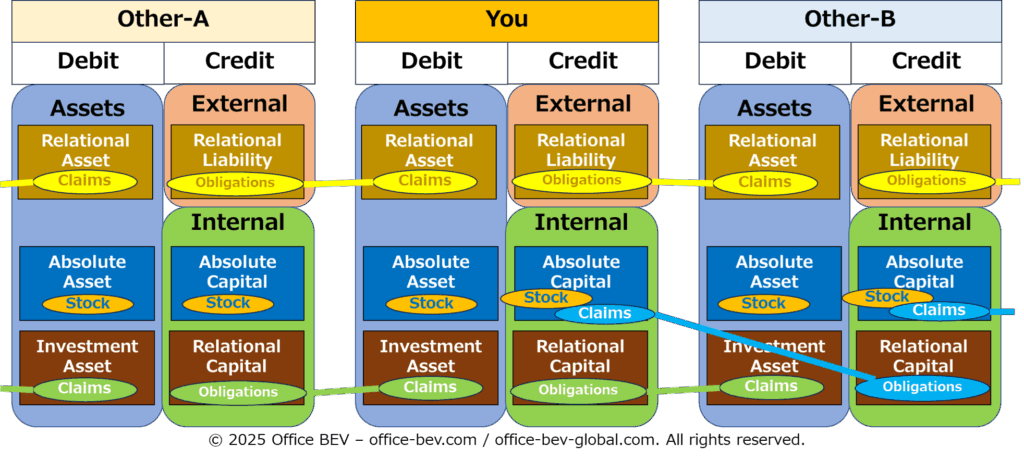

<Central BS connected to other entities via flow structures>

8. Conclusion — The Path to Surplus

This post explored how assets, once generated, take on distinct structural forms—and how those forms can be systematically classified within the BS. We organized these patterns along two axes: Stock vs. Flow, and Single-Entity vs. Inter-Entity.

From this, we identified eight types of asset movements—four stock-based and four flow-based—each representing a unique way in which assets are created, moved, and recovered.

These movement patterns then informed a structural reclassification of the BS into six asset typologies: three on the debit side (Asset Status) and three on the credit side (Asset Sources).

This framework goes beyond conventional accounting terms and redefines the BS as a dynamic structure of generation and transformation.

Yet one fundamental question remains:

Where does surplus come from?

In the next post, we will explore the nature of surplus—the “increase” that appears through these asset flows—and how it relates to both productive activity and inter-entity trust.

<Appendix> Visual Summary — Asset Movement & Typology Framework

The following summary consolidates all movement and classification types covered in this post, offering a visual map of the asset structure framework.

Asset Movement Typologies (4 Quadrants, 8 Types)

[1] Self-Contained Stock Changes (Single-Entity × Stock)

(1) Single-Entity Co-Generation & Co-Extinction

[2] Inter-Entity Stock Transfers (Inter-Entity × Stock)

(2) Involuntary Transfer (Unilateral / Without Intent)

(3) Voluntary Transfer (Unilateral / With Intent)

(4) Mutual Exchange (Bilateral)

[3] Self-Contained Flow Cycles (Single-Entity × Flow)

(5) Consumption Flow

(6) Operational Flow

[4] Inter-Entity Flow Cycles (Inter-Entity × Flow)

(7) Lending Flow

(8) Investment Flow

[1] Self-Contained Stock Changes(Single-Entity × Stock)

[2] Inter-Entity Stock Transfers (Inter-Entity × Stock)

[3] Self-Contained Flow Cycles (Single-Entity × Flow)

[4] Inter-Entity Flow Cycles (Inter-Entity × Flow)

Asset Typologies (6 Types)

[Debit Side: Asset Status]

• Absolute Assets — Stock-based, no external relation

• Relational Assets — Claims from lending, with repayment duty

• Investment Assets — Claims from investing, return-based

[Credit Side: Asset Sources]

• Relational Liabilities — Obligations from borrowing / External Sources

• Relational Capital — Obligations from investment, return-based / Internal Sources

• Absolute Capital — Stock-based, internally generated or converted from claims / Internal Sources

[Central BS connected to other entities via flow structures]

2 thoughts on “Structural Analysis (2): The Structure of Assets — The Forms of Stock and Flow”

Comments are closed.