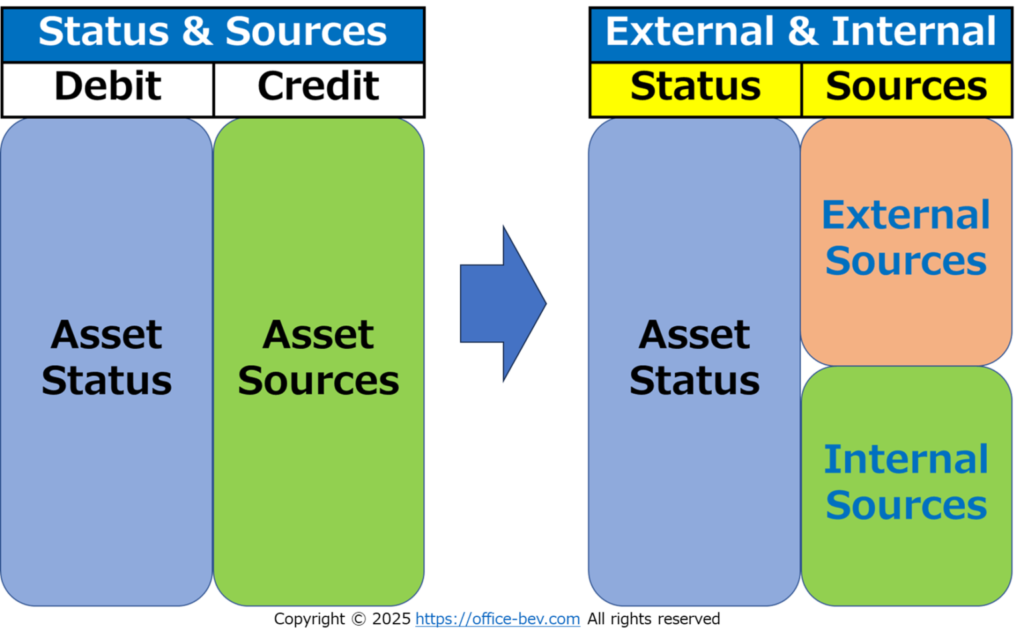

External & Internal

In this post, we explored the basic structure of the BS by abstracting it beyond its traditional accounting role. We demonstrated:

BS consists of a binary framework: asset status (debit) vs. asset sources (credit)

The credit side can be further divided into external sources (with obligations) and internal sources (without obligations).

By applying this binary framework, we showed how the BS can be a universal tool for analyzing fields such as money, thought, power, and technology, and more.

Furthermore, we connected this to the three perspectives—Fiction, Domains, and Relations—from the previous post.

Ultimately, the BS is not merely a financial tool—it is a powerful lens for understanding the structure of the world.

→ See the full article :

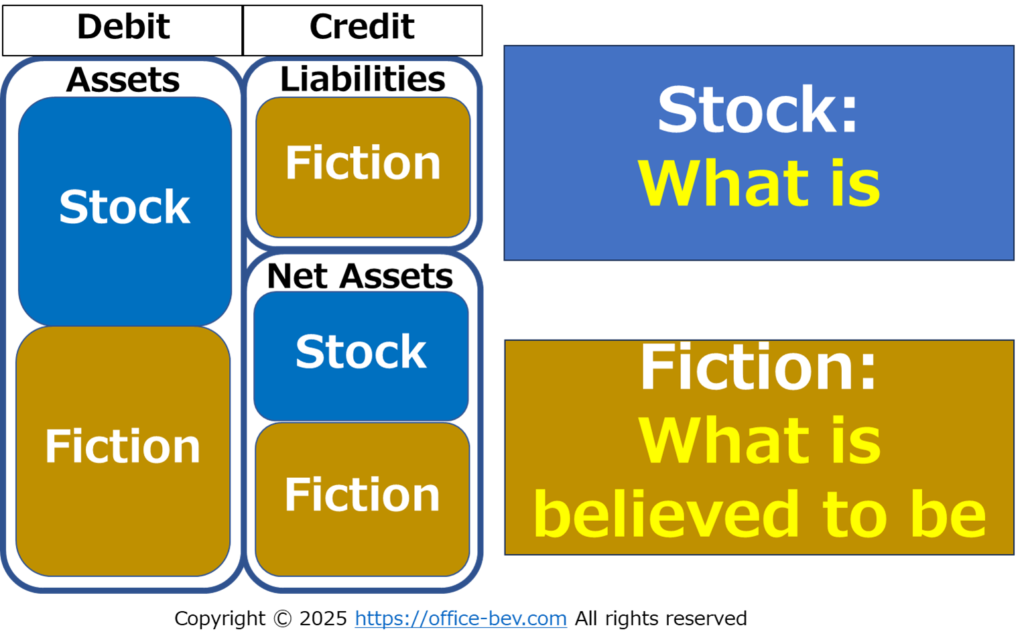

Fiction & Stock

The balance sheet is more than a static record of assets and liabilities. It is a dual structure: a synthesis of realized stock and fictional value grounded in social trust. By interpreting the BS in terms of what is and what is believed, we uncover the deeper foundations of modern financial systems—where fiction, far from being deceptive, becomes the engine of coordination, investment, and collective imagination.

→ See the full article :

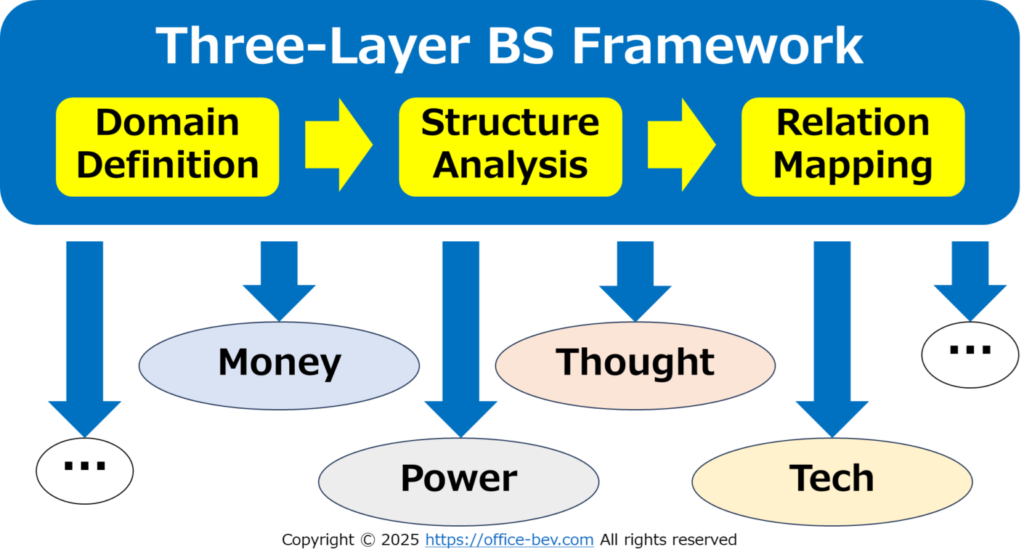

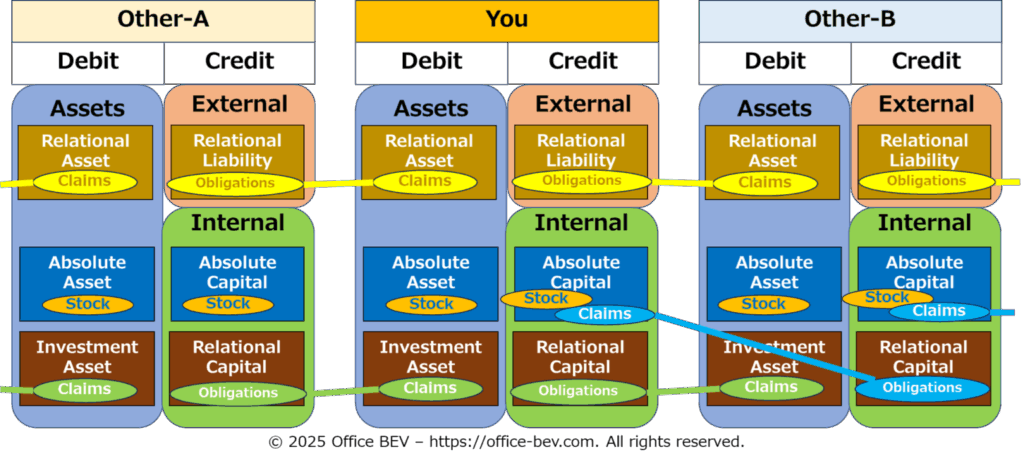

Three-Layer Balance Sheet Framework

The Three-Layer Framework offers a conceptual lens to interpret the world through balance sheet thinking—across domains, the structures of fiction and stock, and relational dynamics.

Each layer functions as an independent analytical perspective, yet together they form a continuous and interconnected flow: domain definition, structure analysis, and relation mapping.

Through this framework, we apply the same fundamental questions across a wide range of phenomena:

Whose structure are we analyzing? What is it made of? And how is it embedded in relations?

→ See the full article :

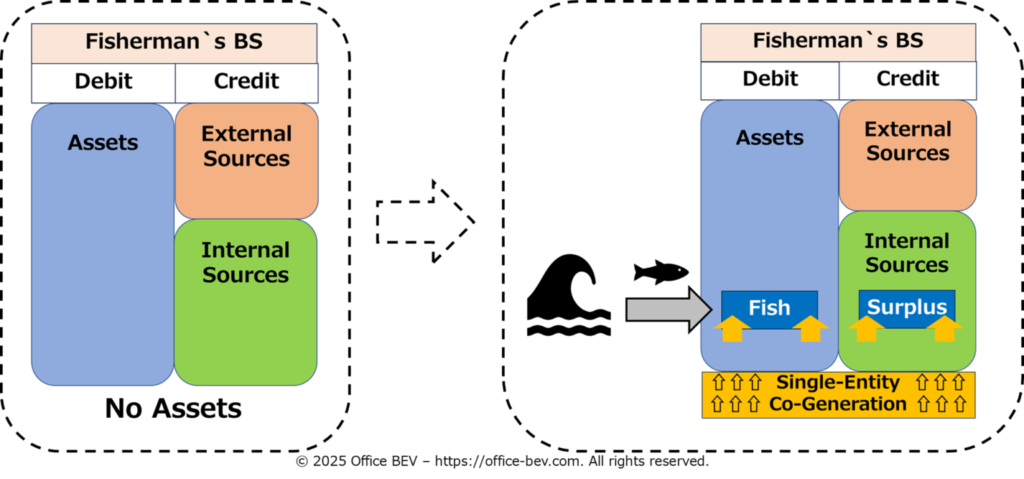

The Genesis of Assets — Where Stock and Flow Begin

How are assets created from nothing?

This article explores the very beginning of asset formation using the Three-Layer BS Framework. It introduces the dual processes of asset creation—within a single entity and between entities—and reveals how stock assets and flow assets first emerge.

By tracing this layered genesis, the article lays the groundwork for the next in the series: an exploration of the structural nature of assets within the balance sheet.

→ See the full article :

The Structure of Assets — The Forms of Stock and Flow

This post explored how assets, once generated, take on distinct structural forms—and how those forms can be systematically classified within the BS. We organized these patterns along two axes: Stock vs. Flow, and Single-Entity vs. Inter-Entity.

From this, we identified eight types of asset movements—four stock-based and four flow-based—each representing a unique way in which assets are created, moved, and recovered.

These movement patterns then informed a structural reclassification of the BS into six asset typologies: three on the debit side (Asset Status) and three on the credit side (Asset Sources).

This framework goes beyond conventional accounting terms and redefines the BS as a dynamic structure of generation and transformation.

Yet one fundamental question remains:

Where does surplus come from?

In the next post, we will explore the nature of surplus—the “increase” that appears through these asset flows—and how it relates to both productive activity and inter-entity trust.

→ See the full article :

→ See Visual Guide to Asset Structures :

The Generation of Surplus

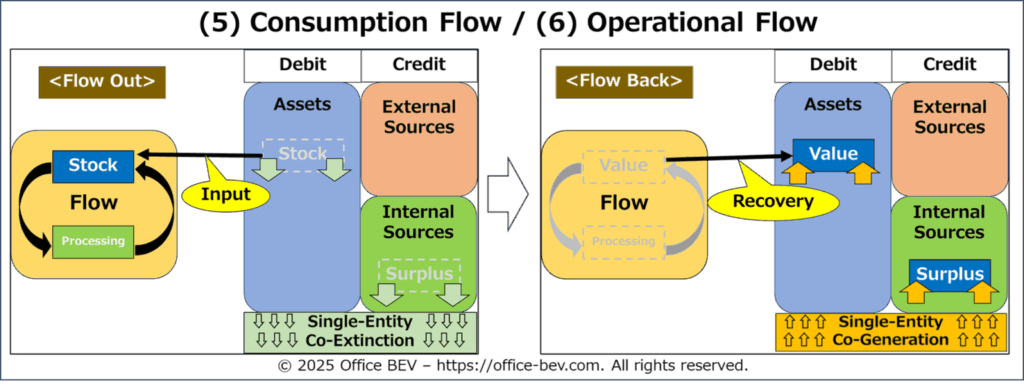

his article addressed the central question: Where does surplus come from?

By examining all eight types of asset movement introduced earlier, we find that only Self-Contained Flow Cycles—namely, Consumption Flows and Operational Flows—have the structural potential to generate surplus.

Within these cycles, Three Core Components—Pure Stock Assets (PSA), Labor Power (LBR), and Money (MNY)—circulate through two interdependent flows. In Consumption Flows, PSA is used to generate LBR. In Operational Flows, LBR and other assets are deployed to generate PSA and MNY. These two flows sustain each other: Consumption Flows depend on PSA regenerated through Operational Flows, while Operational Flows are activated by LBR generated through Consumption Flows. Surplus arises when the value recovered within this regenerative cycle exceeds the original input.

This is the structural answer to surplus: it emerges only when value flows internally and regeneratively within Self-Contained Flow Cycles—through the dual system of Consumption Flows and Operational Flows.

→ See the full article :

The Sources of Surplus

This post took a deeper look into the internal structure of these cycles to identify how surplus is actually generated and what its sources are, where even non-monetary assets must be measured and recognized in monetary terms for surplus to be identified.

We first confirmed that self-contained flow cycles can be divided into two types: Primary Development, which completes within a single entity, and Secondary Development, which extends into Inter-Entity transactions.

Within Primary Development, we identified two types of surplus generation:

- The recovery of labor through Consumption Flows enabled by PSA

- The recovery or creation of PSA through labor-driven Operational Flows

Money, however, does not appear in primary development.

To investigate monetary surplus, we turned to secondary development, which includes Exchanges, Lending Flows, and Investment Flows.

But as already shown in Structural Analysis (3) – Part 1: The Generation of Surplus, these asset transfers do not generate surplus in themselves.

Therefore, to trace the origin of monetary surplus, we had to look beyond secondary development.

Ultimately, all monetary inflows—when followed back to their structural root—lead us to one conclusion: money issuance.

In summary, surplus originates from three distinct sources:

- Labor-based surplus: generated by PSA through Consumption Flows

- PSA-based surplus: generated through labor-driven Operational Flows

- Monetary surplus: derived externally from money issuance

→ See the full article :

The Transformation of Assets

Assets undergo Movement—the cycle of Generation, Transfer, and Extinction.

These movements, when interlinked through Structural Layering and Domain Jumps, result in Structural Transformation.

In this article, we have explored how assets connect, evolve, and circulate within complex relational structures. We approached this question through the lens of the Grand Circulation Structure of Assets—Generation, Transfer, and Extinction—while focusing on the structural transformation processes embedded in the Transfer phase.

Within the Transfer phase, we confirmed the Evolutionary Model of Asset Transfer, which traces the development from Single-Entity to Inter-Entity, from Stock to Flow, and finally from Flow to Layered Flows, where transformation takes place.

In this phase of Asset Transformation, we observed two primary forms: Stock Transformation and Flow Transformation.

The latter arises when Structural Layering of Flow Elements triggers Domain Jumps, which in turn drive the creation of Layered Flow Structures that enable deeper and more diversified forms of transformation.

These layered flows reveal increasing structural complexity, progressing through:

Entity Shift (Externalization), Internal Hierarchy (Nesting), Proliferating Links (Interlinkage), and Role Inversion (Cross-Generation).

(Insert the overall illustration here)

From this perspective, assets should not be viewed merely as objects or conventional claims, but as relational structures—emerging within flows, evolving through layered structures and interconnections, and continually transforming their meaning and position within the broader system of circulation.

→ See the full article :